Education

Ask any investor when to buy and you'll hear confident answers: when valuations look attractive, when fundamentals improve, when technicals align. Ask when to sell? Silence. Or worse, a cascade of emotionally-driven rationalizations that sound strategic but systematically destroy returns.

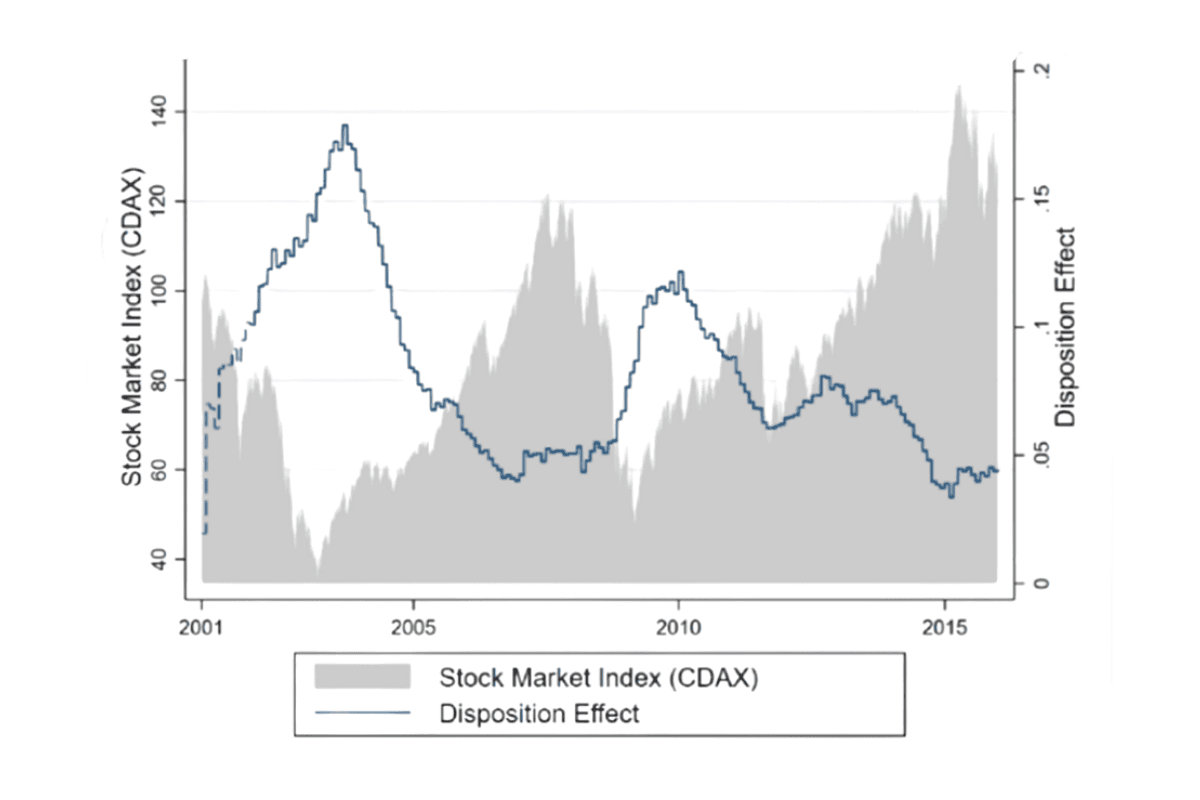

Terrance Odean's landmark 1998 research analyzing 10,000 brokerage accounts found investors sold winning stocks 50% more readily than losing stocks. The kicker? The winners they sold subsequently outperformed the losers they held by 3.4% annually. This pattern—holding losers too long while selling winners too early—has been documented across markets, time periods, and investor types for decades.

Selling isn't just the other side of buying. It's where behavioral biases compound, where tax considerations multiply, and where the gap between professional discipline and emotional decision-making becomes most visible. Here's how to know when selling makes sense—and when you're just rationalizing a mistake.

The Behavioral Trap: Why We Hold Losers and Dump Winners

The disposition effect—the tendency to realize gains quickly while postponing losses—isn't a minor quirk. Studies show it costs the average investor between 3.2% and 5.7% annually in returns. The psychology is predictable:

Loss aversion kicks in: Research from behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky demonstrates that losses feel approximately twice as painful as equivalent gains feel pleasurable. When you're underwater on a position, selling makes that pain real. Holding preserves hope.

Mental accounting distorts reality: Investors treat unrealized losses as "not real yet" while realized losses trigger regret and self-blame. This creates perverse incentives to hold deteriorating positions simply to avoid admitting error.

The sunk cost fallacy compounds: The more time and emotional energy you've invested researching and monitoring a position, the harder it becomes to sell—even when the original thesis has clearly broken.

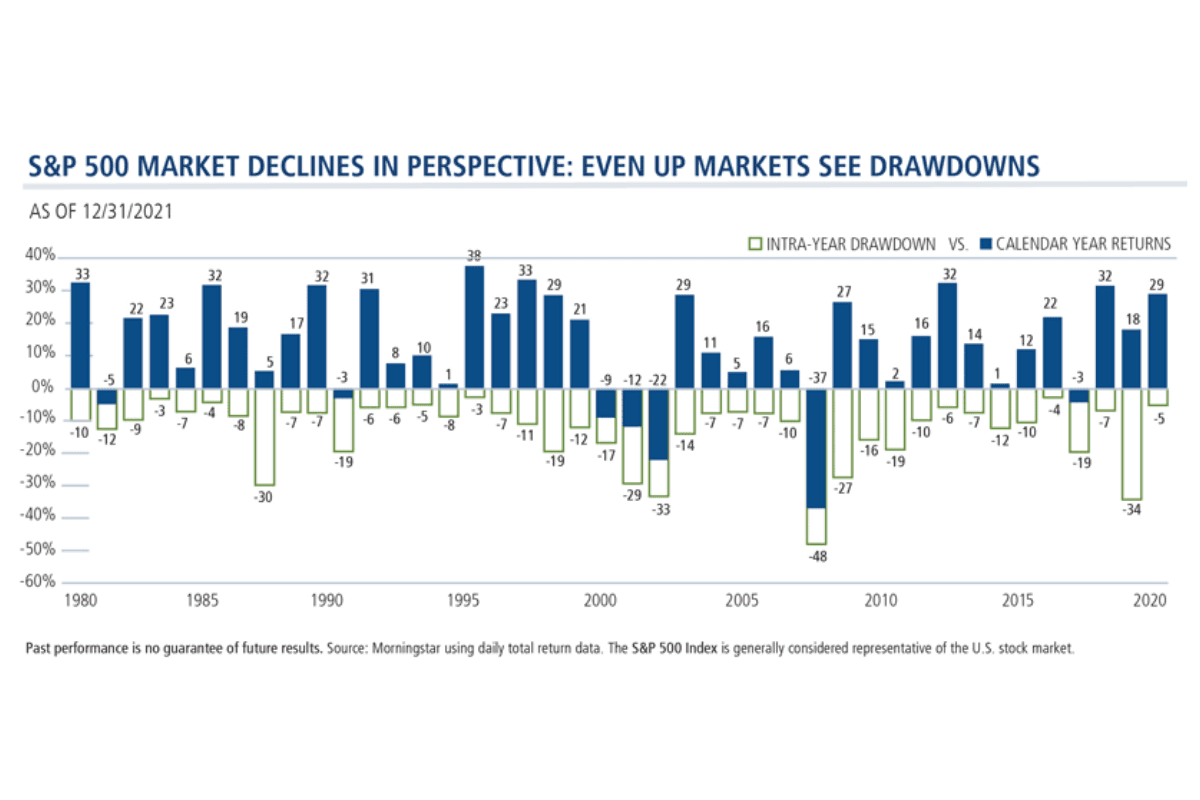

Analysis from DALBAR found that in 2022, the average equity investor underperformed the S&P 500 by 3.06%, largely due to panic-selling during downturns and missing subsequent recoveries. The pattern is consistent: investors sell at exactly the wrong time because emotion overrides strategy.

Valid Reasons to Sell: When Strategy Trumps Emotion

Selling should be driven by strategy, not sentiment. Here are the legitimate triggers:

1. The Investment Thesis Broke

If the fundamental reasons you bought the stock no longer apply, sell regardless of whether you're up or down. Examples include:

Market share deterioration: Competitors are winning with superior products at better prices

Management missteps: Leadership takes on excessive debt or makes reckless acquisitions

Business model disruption: Technology or regulation fundamentally alters the competitive landscape

Consistent earnings misses: Not one-off disappointments, but systematic underperformance against guidance

John Maynard Keynes famously said, "When the facts change, I change my mind." The challenge isn't recognizing change—it's overcoming the emotional resistance to admitting you were wrong.

2. Portfolio Rebalancing Requires It

Vanguard research shows portfolios with more than 20% in a single position see significantly worse risk-adjusted returns. When winners run, they can create dangerous concentration:

A position that was 10% of your portfolio three years ago might now be 35%

You're not diversified—you're overexposed to a single company's fortunes

Trimming back to target allocation isn't "taking profits"—it's risk management

Strategic rebalancing forces disciplined selling of appreciated assets and redeployment into underweighted areas. Studies suggest this mechanical approach adds 35-50 basis points annually through systematic buy-low, sell-high behavior.

3. Tax-Loss Harvesting Makes Mathematical Sense

Selling losers strategically can offset gains and reduce your overall tax burden. Vanguard estimates effective tax-loss harvesting adds 50-100 basis points annually to after-tax returns over time.

The strategy works because:

Realized losses offset short-term and long-term gains

You can deduct up to $3,000 in net losses against ordinary income annually

Excess losses carry forward to future years

You can immediately buy a similar (but not identical) security to maintain market exposure

Critical: Don't let tax considerations drive strategy. Tax-loss harvesting should complement sound investment decisions, not replace them.

4. Valuation Has Become Indefensible

When a stock's valuation meaningfully exceeds both historical norms and reasonable forward projections, trimming makes sense. Current market data shows the S&P 500's total market cap to GDP ratio (the "Buffett Indicator") at 223.9%—significantly above the historical average of 100%.

Consider selling when:

P/E ratios exceed historical ranges by multiple standard deviations without corresponding earnings growth acceleration

The market is pricing in perfection that leaves no margin for disappointment

Comparable companies in the sector trade at dramatically lower multiples for similar fundamentals

Important distinction: Selling because something is "expensive" differs from selling because valuation implies negative expected returns. Markets can stay overvalued longer than you can stay rational.

5. You Need the Capital for a Planned Goal

Life happens. Sometimes selling has nothing to do with the investment and everything to do with your circumstances:

Retirement withdrawals following a predetermined sequence

Down payment on a home after hitting your savings target

Education funding when tuition bills arrive

Emergency expenses that require immediate liquidity

This is why financial planning precedes investing. Knowing your time horizon and liquidity needs prevents forced selling during inopportune market conditions.

Red Flags: When You're Selling for the Wrong Reasons

These triggers feel strategic but often signal emotional decision-making:

"The Stock Is Down—Time to Cut My Losses"

Price decline alone means nothing. Charles Schwab research emphasizes distinguishing between:

Temporary volatility vs. fundamental deterioration

Market overreaction vs. justified repricing

Technical factors vs. changed business realities

If the business remains sound and your thesis intact, price weakness might be an opportunity to add, not exit.

"I'm Taking Profits While I Can"

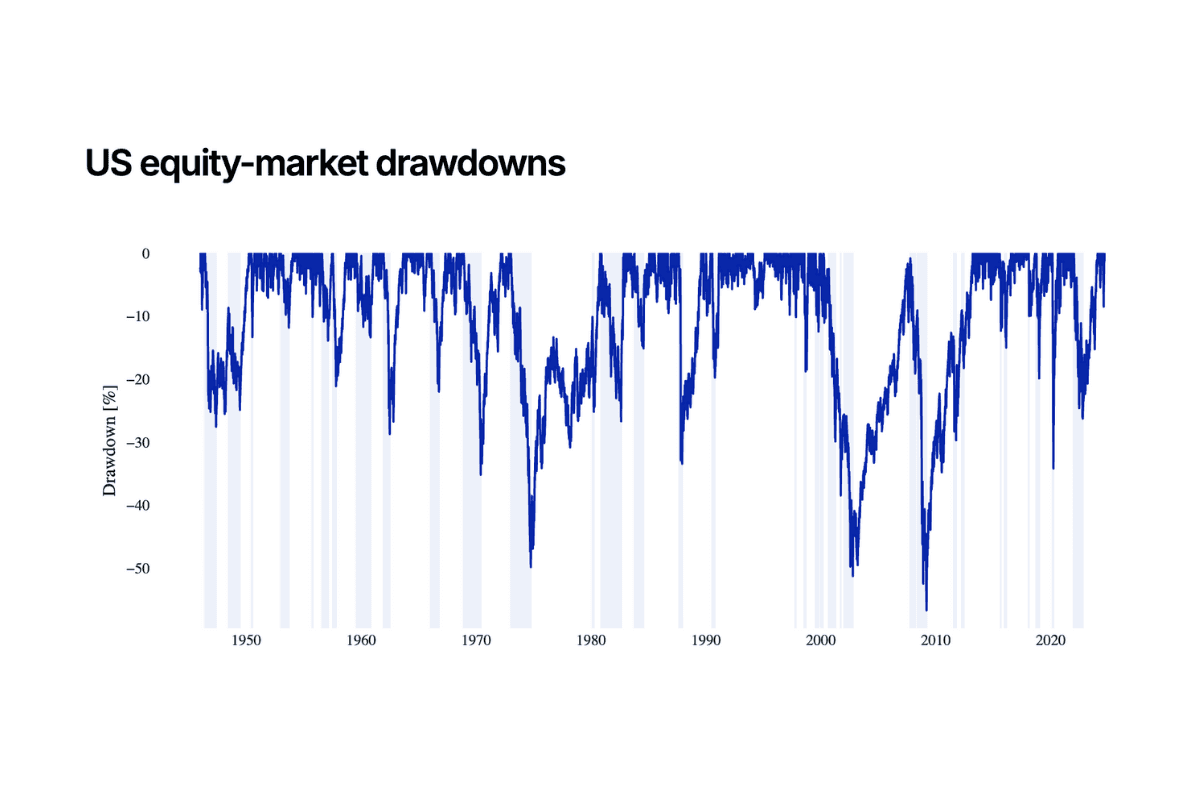

The instinct to lock in gains feels prudent but often leaves significant returns on the table. Morgan Stanley analysis of top-performing stocks from 1985-2024 found they averaged 72% drawdowns before recovering and continuing higher.

Amazon went from $106 in 1999 to $6 in 2001—an 94% drawdown—before eventually trading above $3,000 per share. Selling "to take profits" at $106 would have destroyed generational wealth.

"Everyone's Talking About This Position"

Herd behavior works both ways. Analysis from Wilmington Trust shows that corrections of 5-15% happen on average once every three years. Selling because "everyone else is worried" often means selling near the bottom.

The crowd is usually wrong at extremes—both euphoric peaks and panicked troughs.

The Tax Dimension: Why Holding Costs Less Than You Think

Every sale triggers a taxable event. At the highest brackets, combined federal and state rates can approach 40% on short-term gains, 25-30% on long-term gains.

This creates a massive hurdle: Research from BBH demonstrates that to justify selling a position with embedded gains, the after-tax proceeds need to earn materially higher returns in the new investment.

Example: You're sitting on a $500,000 gain in a concentrated position. Selling triggers $150,000 in taxes (at 30%). Your $500,000 becomes $350,000 to redeploy. The new investment needs to outperform your current position by enough to overcome this starting disadvantage.

The math favors holding in many cases—which is why tax-efficient portfolio transition strategies matter far more than one-time selling decisions.

Building a Systematic Sell Discipline

Professional investors don't rely on gut feel. They establish frameworks:

Set Thesis-Based Exit Criteria Upfront

When you buy, document:

The 3-5 factors that would invalidate your thesis

Valuation levels where risk/reward becomes unfavorable

Time horizons for the thesis to play out

Merrill Lynch research emphasizes that sell discipline requires the same rigor as buy discipline—it's part of the same investment process, not an afterthought.

Rebalance Systematically, Not Reactively

Portfolio drift happens naturally. Setting rebalancing thresholds (e.g., when an allocation exceeds target by 5 percentage points) removes emotion from the decision.

Studies from ETF.com show that household-level rebalancing across multiple accounts reduces trading activity and improves tax outcomes compared to account-by-account approaches.

Review Holdings Quarterly, Not Daily

Frequent monitoring amplifies emotional response to volatility. Fidelity data suggests portfolio reviews every 3-6 months provide sufficient oversight without triggering reactive decisions.

Establish a calendar: "I review holdings every quarter and only sell based on my predetermined criteria."

The Modern Advantage: Systematic Over Heroic

Traditional investing required choosing between control and professional management. Modern platforms enable systematic discipline without surrendering oversight:

Algorithm-driven rebalancing that executes tax-efficiently across your entire portfolio

Automatic tax-loss harvesting that captures losses while maintaining exposure

Threshold-based selling that removes emotional decision-making from concentration risk

The shift isn't about giving up control—it's about implementing discipline at scale. Professional investors succeed not because they make better stock picks, but because they maintain systematic processes that prevent behavioral errors from compounding.

The hardest part of investing isn't finding winners. It's knowing when to let them run, when to trim them back, and when to admit a mistake and move on. Most investors get this backwards: they sell winners to "lock in profits" while holding losers to "avoid realizing losses."

The data is unambiguous: this behavior systematically destroys returns. DALBAR's annual research shows the average investor underperforms buy-and-hold strategies by 3-4% annually, with poor selling decisions accounting for much of the gap.

Selling isn't about timing the market or predicting the next move. It's about maintaining discipline, managing risk, and ensuring your portfolio remains aligned with your goals rather than your emotions. That distinction—strategy over sentiment—is what separates investors who compound wealth from those who chase returns.

Modern tools that enforce systematic rebalancing, tax-efficient transitions, and thesis-based exit criteria don't replace judgment. They implement the discipline that emotion makes impossible. That's not a compromise—it's how compound returns actually get built.

Automate any portfolio using data-driven strategies made by top creators & professional investors. Turn any investment idea into an automated, testable, and sharable strategy.