Education

When financial advisors tell you to dollar-cost average into the market, they're not recommending an investment strategy. They're managing your emotions.

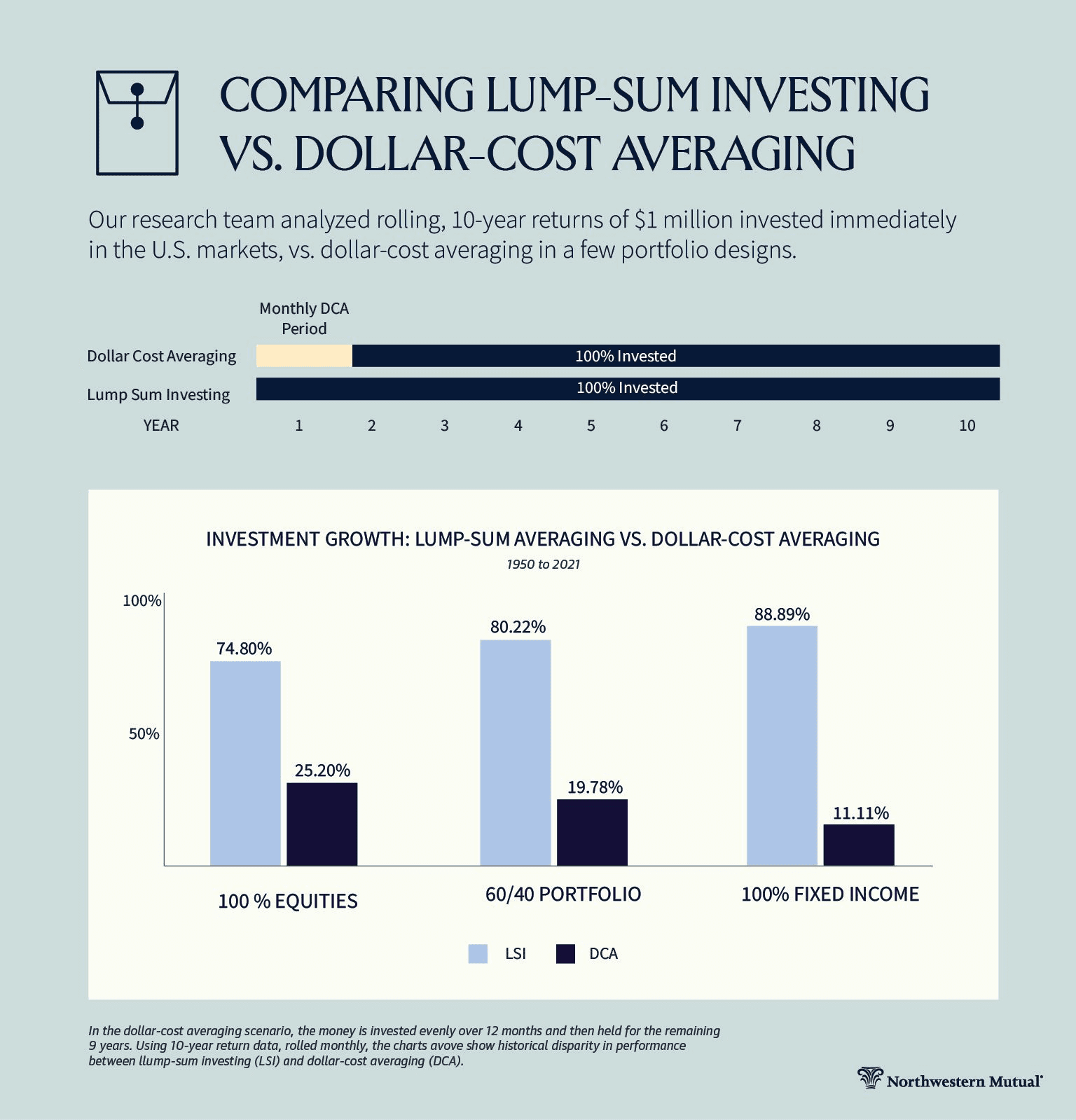

Here's what the data actually shows: lump sum investing outperforms dollar-cost averaging roughly 68% to 75% of the time across major markets and asset allocations. That's not a slight edge—it's a decisive mathematical advantage that's held up across decades of market cycles, from the dot-com crash to the 2008 financial crisis to the pandemic volatility of 2020.

The distinction matters because confusing how you fund an account with how you actually invest creates a gap between what you think you're doing and what's really happening to your money.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Market Timing

Dollar-cost averaging feels intuitive: spread your purchases over time, buy more shares when prices are low, fewer when they're high, and smooth out the volatility. It's the financial equivalent of not putting all your eggs in one basket.

The problem is that markets rise more often than they fall. Historical data shows U.S. stock markets deliver positive returns in approximately 70-75% of all 12-month periods. When you dollar-cost average, you're systematically keeping a portion of your capital in cash—earning minimal returns—while waiting for purchase dates that may come during a rising market.

Key insight: Every dollar sitting in cash during a DCA plan is making an implicit bet that near-term returns will be negative or modest enough to justify the wait.

Vanguard's 2024 research analyzing global markets from 1976 to 2022 found lump sum investing beat dollar-cost averaging 68% of the time after one year. RBC Global Asset Management's data from 1990 to 2024 showed lump sum strategies returned 11.5% annually on average, while a full-year DCA approach delivered just 3.2%. The math is unforgiving: the longer your money sits in cash, the less it compounds.

Why DCA Feels Right But Performs Wrong

The appeal of dollar-cost averaging is rooted in loss aversion—a cognitive bias where potential losses loom roughly twice as large as equivalent gains in our psychological accounting. Research by behavioral economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky established that the pain of losing $100 feels approximately twice as intense as the pleasure of gaining $100.

This creates a powerful emotional dynamic:

Fear of immediate loss (buying at the peak) outweighs the statistical probability of missing gains

The regret of "timing it wrong" feels more acute than the regret of underperformance

Gradual entry into the market provides psychological comfort even when it costs real returns

Dollar-cost averaging doesn't eliminate risk—it just spreads the experience of risk over time, making it feel more manageable. If the market declines over a year, a DCA investor still loses money, just gradually instead of all at once. The total loss is often similar; only the emotional experience differs.

Northwestern Mutual's January 2025 analysis of rolling 10-year returns found that lump sum investing outperformed DCA 75% of the time when invested entirely in stocks. For a 60/40 stock-bond portfolio, that number jumped to 80%. The data is clear: trading mathematical performance for emotional comfort is an expensive tradeoff.

When Dollar-Cost Averaging Actually Wins

DCA does outperform in specific scenarios—namely, sustained market declines or high volatility periods. If you had implemented a DCA strategy starting in early 2008, just before the financial crisis, you would have outperformed a lump sum investment made at the same starting point. By continuing to invest during the downturn, you bought shares at progressively lower prices.

But here's the critical context:

These scenarios represent the minority of market environments

You can't know in advance whether you're entering one of these periods

Attempting to predict them is itself a form of market timing

A 2024 study by PWL Capital examined rolling 10-year periods across six global stock markets and found lump sum investing outperformed DCA on average in all markets tested, with the performance gap widening the longer the DCA period extended.

The only reliable predictor of DCA success is a crystal ball showing imminent market decline—which, inconveniently, doesn't exist.

What an Actual Investment Strategy Looks Like

Here's what separates a real strategy from a funding method: a strategy defines your target asset allocation, rebalancing rules, and risk parameters. It's about what you own and how you manage it, not how you move money into an account.

A proper investment strategy includes:

Asset allocation: Your target mix of stocks, bonds, and other assets based on risk tolerance and time horizon

Rebalancing discipline: Systematic rules for buying and selling to maintain your target allocation as markets move

Risk management: Position sizing, diversification, and downside protection that matches your goals

Tax efficiency: Thoughtful placement of assets across taxable and tax-advantaged accounts

Dollar-cost averaging addresses none of these. It's purely a decision about deployment timing.

Modern portfolio theory and decades of research point to a straightforward approach: determine your optimal asset allocation, invest according to it, and rebalance systematically. Research on threshold-based rebalancing shows that monitoring allocations and only rebalancing when portfolios drift beyond meaningful thresholds tends to outperform both calendar-based and judgment-based approaches.

The sophisticated move isn't timing your entry—it's building a portfolio that can withstand volatility regardless of entry point.

The Real Risk Isn't Timing the Market Wrong

The most dangerous outcome isn't investing at a temporary peak. It's staying on the sidelines entirely, paralyzed by the fear of poor timing.

Consider two scenarios from RBC's analysis of the 2008-2009 financial crisis: a DCA investor who spread $50,000 across six monthly installments during the market's collapse saw their holdings protected relative to a lump sum investor. But the DCA investor who waited and started their six-month plan after markets had already fallen—or worse, who never started at all—missed the entire recovery.

The hierarchy of investment decisions:

Being in the market beats being out of it

Being in with the right asset allocation beats being in with the wrong one

Being in sooner beats being in later (in most market environments)

Dollar-cost averaging can serve a legitimate purpose for risk-averse investors who might otherwise abandon their investment plans during volatility. If gradual entry keeps you invested rather than sitting in cash indefinitely, it's worth the cost. But be honest about what you're paying for: emotional insurance, not superior returns.

Beyond the Binary: Modern Tools Change the Game

The lump sum versus DCA debate assumes manual implementation and large discrete sums to invest. But automated platforms and algorithmic strategies have created more nuanced approaches.

Modern portfolio management tools can:

Implement systematic rebalancing that captures some benefits of buying during declines without the opportunity cost of sitting in cash

Use tax-loss harvesting to turn volatility into a tax advantage rather than just an emotional challenge

Deploy rules-based strategies that respond to market conditions without requiring you to make fraught timing decisions

Platforms that combine automated asset allocation, intelligent rebalancing, and tax optimization treat deployment timing as one variable within a broader strategic framework—not as the primary decision.

The question shifts from "Should I lump sum or DCA?" to "How do I build a resilient portfolio that performs well across various market scenarios?" That's a much more productive conversation.

The Bottom Line

Dollar-cost averaging isn't wrong—it's just not what most people think it is. It's a behavioral tool that makes investors comfortable enough to get skin in the game, not a performance-enhancing strategy. The data is unambiguous: lump sum investing wins the majority of the time because markets trend upward more often than they decline.

If you have a lump sum to invest and are purely focused on maximizing expected returns, the math favors immediate deployment into your target asset allocation. If market volatility triggers panic selling, dollar-cost averaging may keep you invested when you'd otherwise flee. Just know what you're optimizing for.

The sophisticated investor recognizes that deployment timing is a footnote to the main text of asset allocation, diversification, and systematic rebalancing. Build a strategy that can weather volatility regardless of entry point, implement it consistently, and let compounding do the heavy lifting.

That's not just better than dollar-cost averaging. It's better than trying to time anything at all.

Automate any portfolio using data-driven strategies made by top creators & professional investors. Turn any investment idea into an automated, testable, and sharable strategy.